Adrian York, University of Westminster

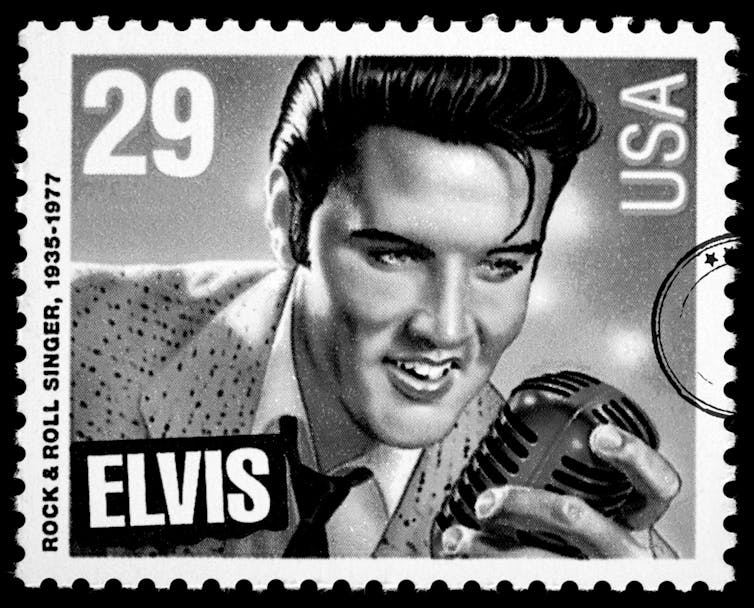

Much of the mythology that surrounds Elvis Presley, who died 40 years ago, tends to surround his rags to riches story, his film-star looks, his outrageous stage outfits, his marriage to child bride Priscilla and his descent into overindulgence and drug addiction at his Graceland mansion. In death, Elvis has become to millions a kind of cautionary tale of celebrity, sex and scandal that has at times threatened to engulf his legacy. But perhaps the most important part of that legacy is his voice – a voice that has sold more than a billion records.

Etched into the grooves of all those records was the sound of an extraordinary singer with a range of more than two octaves, wonderful control, tone and vibrato and the ability to cross genres effortlessly. Record producer John Owen Williams says of Elvis:

People talk of his range and power, his ability and ease in hitting the high notes. But the real difference between Elvis and other singers was that he could sing majestically in any style, be it rock, country, or R&B – because he had soul. He sang from the heart. And that is what made him the greatest singer in the history of popular music.

Elvis grew up in Tupelo, Mississippi, and moved with his family to Memphis, Tennessee, when he was 15. He was immersed in the pop and country music of the time as well as the gospel sounds from his church. Beale Street in Memphis was a centre for blues and R&B so those influences would have also have been a major factor in Elvis’ musical development. As Pricilla was to explain years after his death, young Elvis’ eclectic record collection included:

Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, gospel and black music. There was rhythm and blues artist Joe Turner, Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson, Chuck Berry, the Righteous Brothers … and even Duke Ellington and Glen Miller.

But it was their shared love of the star American tenor Mario Lanza, she added, “that was really the link between the two of us”. Lanza’s hugely popular “bel canto” classical tenor approach fused with the roots styles surrounding Elvis created the core of his singing style. Opera star Kiri Te Kanawa told Michael Parkinson that the young Elvis had the greatest voice she had ever heard. The tenor Placido Domingo similarly enthused in an interview in Spanish magazine Hola in 1994: “His was the one voice I wish to have had.” Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel told The New York Times in 2007 that Presley was: “… very classically orientated with his voice and diction and very sincere and wanting to get everything perfect.”

Learning process

Elvis’ musical career can be divided into four eras: the early years in the 1950s singing rock’n’roll, country and gospel; the transition to pop in 1960; the renaissance years surrounding the 1968 TV Comeback Special and the still glorious melancholy of his final work in the late 1970s. But what was it about his voice that spoke so directly to so many people across this time span? Cathryn Robson, a senior lecturer in voice and music performance at the University of Westminster, said:

Elvis was technically fearless and instinctive in his use of technique. In his early material in particular it is as if his voice is finding and creating the lyrics as he is singing them.

To really understand Elvis’ sound we have to go back to the recordings. One of the hallmarks of Elvis’ vocal approach is a combination of his large range with the unusual ability to move seamlessly between his tenor and baritone voices. Combined with his range, he has great control over the placement of the voice in the different resonant centres such as the chest, head and the pharynx at the back of the mouth which affects the vocal tone. https://www.youtube.com/embed/gj0Rz-uP4Mk?wmode=transparent&start=0

The rock’n’roll classic Jailhouse Rock from 1957 features a distorted high tenor vocal combined with sloppy lyrical articulation in an explosive performance. The contrast with the pure, clean tone of Elvis’ 1960 rendition of the gospel classic Milky White Way with its great blend of resonance between the chest and head voices is clearly apparent.

In Can’t Help Falling in Love from 1961, Elvis explores the richness of his baritone range moving to a gorgeous light baritone in the bridge of the song. Guitar Man from 1967 – the track that gave the first hint of his mid-60s “comeback” – features a “speak-singing” approach described by Robson as a singer’s “technical holy grail”. https://www.youtube.com/embed/DcJac6OykfM?wmode=transparent&start=0

The 1972 song Burning Love, Elvis’s final hit in his lifetime, features another sound altogether – a tight forceful vocal tone with the voice bursting out of his pharynx over a driving rock track.

Technical prowess

Elvis had a brilliant ability to control the attack and ending of each note. If we listen the 1954 Sun Records recording of Blue Moon of Kentucky we can hear Elvis using a technique known as “glottal onset and offset” – a technique in which the vocal folds in the larynx are closed at the start of a note and closed with extra emphasis at the end of the note – to achieve clarity of attack and an amazing rhythmic bounce in his vocal performance. That ability to drive the rhythm is also present in the 1963 hit Viva Las Vegas in which Elvis effortlessly accents the melody to give a rhythmic shape to each phrase. https://www.youtube.com/embed/ui0EgRsFVN8?wmode=transparent&start=0

The 1960 release of It’s Now Or Never marked Elvis’ transition to pop. The song was a reworking with specially commissioned lyrics of O Sole Mio, a signature hit for Mario Lanza. Alongside the operatic “bel canto” approach Elvis sings the song using a technique known as “devoicing” which creates sudden drops in the dynamic of the vocal. This allows Elvis to mark the emotional fragility in the lyric creating as Robson notes “a mix of assertiveness and vulnerability”.

A crucial element in Elvis’ sonic signature was his use of vibrato. The final Battle Hymn of the Republic’ segment of the 1972 recording of An American Trilogy features the sound of his vocal folds vibrating together in all their glory creating a sound that has been much copied in pop music but never bettered.

Elvis was much more than just a collection of vocal techniques – and as a singer had to overcome the sometimes mediocre material he was saddled with. As his legend fades we will be left with the multiple sounds of his voice: tender, aggressive, loving, uncertain, swaggering, pious and sexual – all delivered with a consummate technical virtuosity that was as much assimilated as studied. https://www.youtube.com/embed/WWVMXLSS1cA?wmode=transparent&start=0

But enough of these words. Go and listen to the recordings for yourselves – or, as Elvis sang in the 1968 movie Live A Little, Love A Little, let’s have A Little Less Conversation, A Little More Action.

Adrian York, Senior Lecturer in Commercial Music Performance, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.