Joshua P. Nudell, Westminster College

Most of us take big and small risks in our lives every day. But COVID-19 has made us more aware of how we think about taking risks.

Since the start of the pandemic, people have been forced to weigh their options about how much risk is worth taking for ordinary activities – should they, for example, go to the grocery store or even turn up for a long-scheduled doctor’s visit?

As a scholar of ancient Greek history, I am interested in what the classics can teach us about risk-taking as a way to make sense of our current situation.

Greek mythology features godlike heroes, but Greek history was filled with men and women who were exposed to great risks without the comforts of modern life.

The iron generation

One of the earliest written works in Greek is “Works and Days,” a poem by a farmer named Hesiod in the eighth century B.C. In it, Hesiod addresses his lazy brother, Perses.

The most famous section of “Works and Days” describes a cycle of generations. First, Hesiod says, Zeus created a golden generation who “lived like the gods, having hearts free from sorrow, far from work and misery.”

Then came a silver generation, arrogant and proud.

Third was a bronze generation, violent and self-destructive.

Fourth was the age of heroes who went to their graves at Troy.

Finally, Hesiod says, Zeus made an iron generation marked by a balance of pain and joy.

While the earliest generations lived life free of worries, according to Hesiod, life in the current iron generation is shaped by risk, which leads to pain and sorrow.

Throughout the poem, Hesiod develops an idea of risk and its management that was common in ancient Greece: People can and should take steps to prepare for risk, but it is ultimately inescapable.

As Hesiod says, “summer won’t last forever, build granaries,” but for people of the current generation, “there is neither a stop to toil and sorrow by day, nor to death by night.”

In other words, people face the consequences of risk – including suffering – because that is the will of Zeus.

Omens and divination

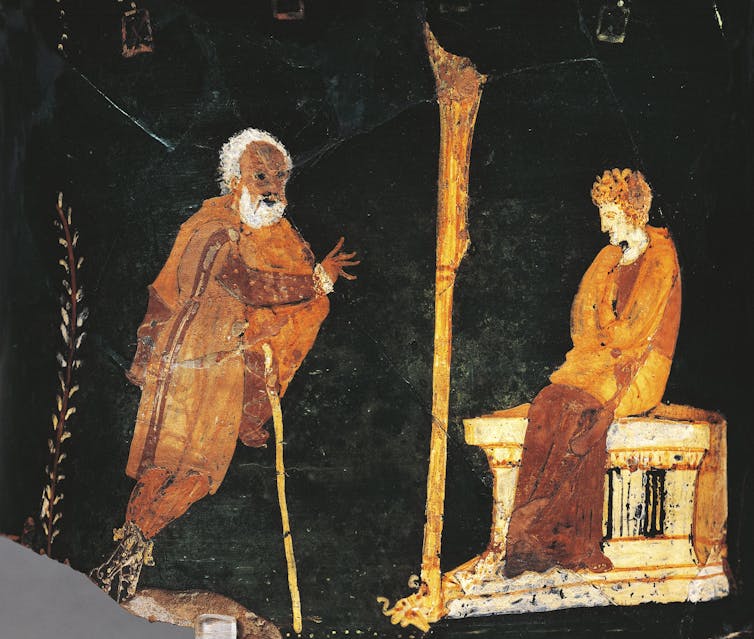

If the outcome of risk was determined by the gods, then one critical part of preparing to face uncertainty was to try to find out the will of Zeus. For this, the Greeks relied on oracles and omens.

While the rich might pay to petition the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, most people turned to simpler techniques to seek guidance from the gods, such as throwing dice made of animal knuckle bones.

A second technique involved inscribing a question on a lead tablet, to which the god would provide an answer such as “yes” or “no.” These tablets record a wide range of concerns from ordinary Greeks. In one, a man named Lysias asks the god whether he should invest in shipping. In another, a man named Epilytos asks whether he should continue in his current career and whether he ought to wed a woman who shows up, or wait. Nothing is known about either man except that they turned to the gods when confronted with uncertainty.

Omens were also used to inform almost every decision, whether public or private. Men called “chresmologoi,” oracle collectors who interpreted the signs from the gods, had enormous influence in Athens. When the Spartans invaded in 431 B.C., the historian Thucydides says, they were everywhere reciting oracular responses. When plague struck Athens, he notes that the Athenians called to mind just such a prophecy.

Chresmologoi played so much of a role in bolstering public confidence that the wealthy Athenian politician Alcibiades privately contracted them as spin doctors in order to persuade people to overlook the risks of an expedition to Sicily in 415 B.C.

Mitigating risks

For the Greeks, putting faith in the gods alone did not fully protect them from risk. As Hesiod explained, risk mitigation required attending to both the gods and human actions.

Generals, for example, made sacrifices to gods like Artemis or Ares in advance of battle, and the best commanders knew how to interpret every omen as a positive sign. At the same time, though, generals also paid attention to strategy and tactics in order to give their armies every advantage.

Neither was every omen heeded. Before the Athenian expedition to Sicily in 415 B.C., statues sacred to Hermes, the god of travel, were found with their faces scratched out.

The Athenians interpreted this as a bad omen, which may have been what the perpetrators intended. The expedition sailed anyway, but it ended in a crushing defeat. Few of the people who left ever returned to Athens.

The evidence was clear to the Athenians: The desecration of the statues had put everyone in the expedition at risk. The only solution was to punish the wrongdoers. Fifteen years later, the orator Andocides had to defend himself in court against accusations that he had been involved.

This history explains that individuals might escape divine punishment, but ignoring omens and failing to take precautions were often communal rather than individual problems. Andocides was acquitted, but his trial shows that when someone’s actions put everyone at risk, it was a community’s responsibility to hold them accountable.

Oracles and knuckle bones are not in vogue today, but the ancient Greeks show us the very real dangers of risky behavior, and why it is important that risk not be left to a simple toss of the dice.

Joshua P. Nudell, Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics, Westminster College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.